People try something in their team, it works great, and then they go out in the world trying to sell everyone on that practice. We’ve done this too when eXtreme Programming worked much better for us than expected in the early 2000s. When such a “best practice” goes out in the wild, it will work for some, but less so for others. So we end up with “Why you should do Test Driven Development (TDD)” versus “TDD does not work” positions.

This kind of dialectic does nothing to advance our field. We find it more useful to understand how a practice works, why it works, where it works, and where it doesn’t. Over the years, we have been pleasantly surprised to find that some of our favourite practices work in more contexts than we expected. That still does not mean they work everywhere. When a practice is not a good fit, it teaches us something about how it works.

In this post, we will present a different perspective on practices:

A practice fits in a context. It resolves specific forces in a specific context. If we have a minimum of three instances where it works, it constitutes a pattern.

Introduction

Our trade is full of “best practices”, scare quotes intentional. So are the flavour of the months’ “methodologies”, like Agile, Scrum, DevOps, SAFe, Cloud Native, Spec Kit, the list goes on. Vendors, consultants, coaches and enthusiastic employees push these on the organisations they work with.

We saw this with agile. Teams were coached, or often coerced, into adopting Scrum practices like sprints, daily standups, backlog refinements, sprint retrospectives. Roles like product owners and scrum masters were created without much thought as to how they would function to deliver value. How? Through promises of delivering faster, doing more work in less time, “being agile”.

We are using ‘agile’ as an example here, but you might see the same with emerging practices around working with Large Language Models (LLMs) for instance.

Sometimes this works and a team becomes more productive - for some definition of productive, as productivity is ill defined for software teams. Many other teams complain about “all these meetings”, they talk about “rituals”, they’re going through the motions, eagerly waiting to get back to the “real work”, even though the agile coach, scrum consultant, or scrum master explained the why of these practices.

Working in short cycles is a good thing right? Just like checking in every day with the team on progress and impediments, so that we can help each other out? Or reflecting frequently and adjusting the way we work? So what are we missing? Is the team not doing the practices well enough? Do we need to explain more? To the consultant, this may sound like sound advice. To the recipients, this is likely to come across as “you are holding it wrong”.

A different perspective

We think part of the problem is how we think about practices. We often regard a practice in isolation, as something that is a generally good thing to do. This thing has proven itself in the field, therefore we should be able to apply it. We use the practice as a recipe, to achieve “goodness”. No need to determine whether this practice will work - the practice has already proven itself so we don’t need to.

We see practices not as an isolated good or universally proven things you can do, but as patterns.

Patterns

What is a pattern?

We use the pattern concept from Christopher Alexander from his book A Pattern Language:

"Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.”

A pattern describes the context, the problem, and the solution as a field of relationships required to solve the stated problem in that context. The context includes the larger patterns it completes. The pattern description often describes counter-indications for when the pattern is not applicable.

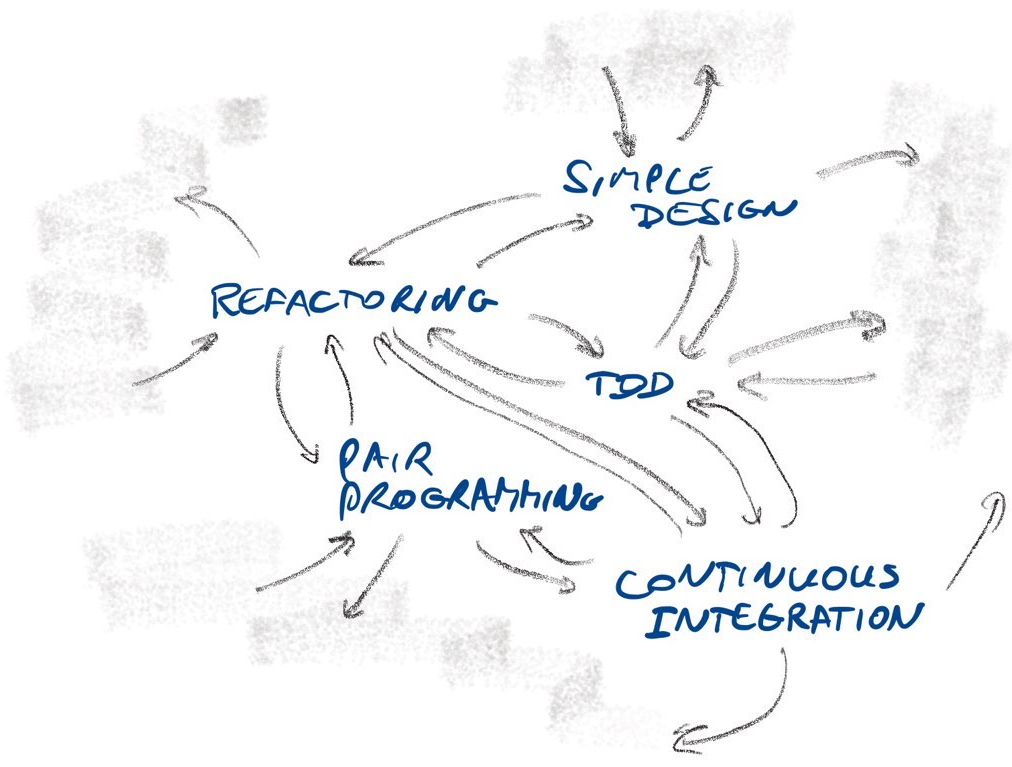

Both eXtreme Programming (XP) and Scrum emerged from the Design Patterns community in the 1990s. Scrum was published as a pattern language in 1998. XP emerged on the C2 Wiki, originally known as the “Portland Pattern repository”.

The first edition of the eXtreme Programming Explained book echoes this, by presenting practices as part of a web of practices which support each other.

So a practice resolves forces in a specific context. That means that whenever we are talking about a practice, or recommending one, or trying to implement one, we need to be aware of the applicable context and how the practice fits.

Take the practice of using a Definition of Done for instance. It is often pushed as a “best practice”, but we have met many teams where the Definition of Done was collecting dust on the wall (or in a corner on Confluence). A Definition of Done is helpful when where there is ambiguity around when feature is done. Agreeing on an explicit checklist of criteria can help the team.

It also means that when we are enthusiastic about a practice, we should present not only the practice itself, but also the forces it intends to resolve, possible consequences, and trade-offs. A nice example is how Jim Shore describes the practice of retrospectives in his Art of Agile Development book, providing contra-indications when retrospectives might not work.

From best to good fit

This also helps getting rid of calling something a “best practice”. A “best practice” implies that there is nothing better and detaches a practice from context. It removes the opportunity to discuss actual fit to the situation at hand or considering trade-offs - “best” implies all trade-offs are in favor of this practice.

If we seek “best” i.e. universally applicable things, these tend to be at a different level, more like principles. A good example are Simon Wardley’s doctrine principles, standard ways of operating and techniques that you almost always should apply. A doctrine pattern like “Focus on user needs” is more abstract than for instance a Definition of Done. This enables generativity for the principles: you have to adjust the fit before applying it to your specific context.

Discovering context

So how do you learn what context a practice is a good fit for? Let’s take a look at how practices are often discovered:

- Someone tries something or observes behaviour. For example, teams tend to work closely together, when there is a urgent production issue. They synchronize work frequently so that they can redirect their efforts while they discover new insights. Someone also observed that when people do a meeting standing up, the meeting tends to be short and focused. This gave rise to daily standups, not just for emergency work but also for normal work, broadening the applicability.

- The person starts sharing this as something that works well. The idea pops up at conferences, at meetups, in blog posts. Their message is basically “this worked for me, I think it is useful for others as well”.

- More people start trying and selling the practice. They advise teams or organisations to start doing it or coach/mentor/guide/force them into doing it.

- As more and more teams are trying it, there will be success and failure stories. This tends to follow the hype cycle, first people are overly enthusiastic, then the “can’t possibly work” critics come along.

Unfortunately, as mentioned in the introduction, the “it works” “no it does not” debate that emerges from step 4 is not very useful. Both success and failure stories are actually useful, because they provide information about the boundaries of bounded applicability and the consequences.

Although much evidence for practices remains anecdotal, often worsened with appeals to authority, there is a growing body of evidence coming from initiatives like the annual DORA research report and the research done by Cat Hicks, which provide more and more insights in what works why.

Implications

So what does this way of looking at practices bring us?

- Regarding a practice in isolation is not useful, and could even be harmful. To apply a practice properly, we need to know which forces it resolves, its trade-offs, consequences, and any counter-indications.

- We don’t find it useful to talk about why a practice works or does not work. Writing an agitated blog post about “why Test Driven Development does not work” is not useful. Sharing how you tried Test Driven Development in a specific situation, where it turned out to be a lot of work with limited benefits does provide useful knowledge.

- Copying a practice that seems to be working for someone else without taking situation and history into account will probably not give the desired results (although you might be lucky).

- Don’t impose or “install” a practice on someone or a system like team, group, or organisation. Focus on how it fits the situation at hand. Disregarding context can backfire - people picking up a dislike for e.g. Test Driven Development because it has been pushed upon them with proper regard for their situation.

- Failure stories are as important as success stories, as long as these are beyond the “I tried this for 30 minutes and it didn’t work”. Failure stories help find boundaries and trade-offs. Furthermore, people learn more from failure stories than success stories.

- A practice is pattern, not a recipe. You cannot follow it blindly and expect a guaranteed outcome. Learning a practice often involves learning skills and know-how. Heuristics can help, as well as stories from others.

- Even after carefully considering context and trade-offs, we find it most effective to introduce a practice as an experiment. The people who will apply the pattern, agree to use the practice to the best of their ability, with plenty of reflection in between, for a significant period of time, say six weeks. The proof (or refutation) of the pudding is in the eating. Look for success or failure indicators, and notice unintended consequences. You might learn something new about context or applicability.

Further reading

- Christopher Alexander, The Timeless Way of Building & A Pattern Language

- Cynefin sense-making framework & the concept of bounded applicability

- Kent Beck, Extreme Programming Explained (1st edition)

- Cat Hicks’ Research on software teams

- Various authors, Scrum, A Pattern Language for Software Development (originally from 1998)

- C2 Wiki

- eXtreme Programming page on the C2 Wiki

- The original Domain Driven Design book was also written as a collection of patterns