User Story Mapping is one of our favourite practices that we often use with clients and in courses. User Story Mapping is an agile product planning practice, with its roots in user centered design. It has been popularized by Jeff Patton.

Mapping user stories in two dimensions

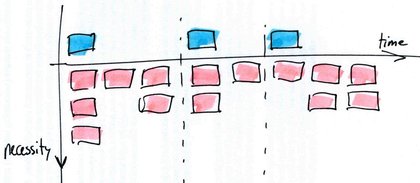

User story mapping offers an alternative for more traditional agile planning approaches like the Scrum product backlog. Instead of a simple list, stories are laid out in a two dimensional map. The map provides a high level overview of the system under development, insight in the value it adds to the users (the horizontal axis), and a way to organize detailed stories into releases according to importance and priority (the vertical axis). The map shows how every user story fits in the full scope.

Releases are defined by creating horizontal slices of user stories, each slice being a release. For the first release, it is recommended to build a walking skeleton - a minimal set of user stories covering all user goals, so that you build a minimal but complete system to validate functionality and architecture early.

An important contribution of user story mapping is its focus on the users, the user goals, and the (system independent) activities/processes that the system should support. This helps the team to focus on why they are building the software - business value instead of feature details.

We love small user stories

We prefer small user stories that can be build in 1 or 2 days. They are easier to estimate, you can deliver working software daily, you get early feedback often, and you get a continuous feeling of accomplishment. The need extensive task planning is reduced, because making a quick list of tasks just in time on an index card is sufficient.

Limitations of traditional agile planning approaches

We ran into a number of limitations of small stories. It becomes increasingly more difficult to understand the system as a whole through all the stories. Some of our customers had trouble seeing the forest for the trees. We were also lacking a way to manage coherent sets of dependent stories. These start off as epics or themes, but once they are split up, it becomes hard to keep track of what belongs to what and how far each theme or epic has been done.

We also ran into limitations of linear backlogs for managing and prioritizing user stories. With lots of small stories and a lack of a good overview, it becomes difficult to prioritize. You spend more and more time on rearranging and refining the backlog instead of delivering working, valuable software.

Release planning - determining what value to deliver when - is a complex problem with multiple dimensions. Reducing it to a one dimensional backlog can work for simple systems, but for most systems we work with, essential details are lost.

The traditional way of agile planning supports working incrementally well. It provides little support for iterative development - building a story by fleshing it out in a number of deliveries. The risk here is that customers expect a user story to be finished in one go, while it might need two or more iterations. Lack of support of iterative development also bears the risk of customers requesting complete, bloated features. Simpler features could be sufficient. But the customer cannot know that until they see the features working in their context.

Last but not least, we frequently encounter developers and customers talking primarily in terms of software features. Teams get lost in solution details without a thorough understanding of the actual problems the software will solve. It’s not only developers failing to speak the customer’s language! We have also encountered customers and users talking databases, fields, screens, instead of focusing on what they actually want to achieve.

User story mapping to the rescue

User story mapping focuses on the different users of the system and their goals. To achieve their goals, users perform activities, consisting of tasks. These are all user-centric - focusing on what the user does, not on features of the software. Features should support the user in doing tasks and achieving goals.

Instead of a linear backlog, you create a map of user activities and tasks. This defines the system at a high level and gives a complete overview of the scope. You put activities and tasks along the horizontal axis. The map then tells the story of the system: the activities describe the bird’s eye view of the scope, the tasks tell how a user actually uses the system. Note that activities and tasks are closely related to business processes. Adapt the terms to your own context.

You define releases based on tasks. You iteratively build the system, fleshing out the different tasks by defining detailed user stories (which are software oriented). The vertical axis of your story map indicates importance: higher up means more important.

You define releases by drawing horizontal slices and moving stories up and down between slices. For the first release you define a walking skeleton - the bare bones of the system, minimal functionality that covers all activities. You defer splitting out the task level stories into concrete, detailed stories until the last responsible moment.

Detailed stories will become ‘done’, activities en tasks are never ‘done’ as a story. You can always put in more features, make it better.

There are no hard and fast rules for story mapping. There are guidelines, but no strict boundaries of what activities, tasks, and stories are. The boundary between user oriented stories and software oriented stories is not strictly defined either.

Benefits

User story mapping brings a number of benefits:

- It helps to keep an overview of the whole system and makes visible what value the system adds, what goals and activities or processes it supports, and how all the small, detailed user stories fit in.

- It facilitates release planning and enables a better conversation about defining delivering value early and managing risks. Building a walking skeleton can give early feedback on market and technical risks.

- By introducing the user’s perspective and the rationale behind the system, user story mapping shifts the dialogue to the actual business value of the software. We only build features when the story map shows a rationale for that feature. A story map helps focus on the essential parts of the system. We have also used story maps to make teams aware that you don’t need to build all those features. A subset is often sufficient to help users achieve their goals.

- By focusing on user goals, activities, and tasks first instead of software features, you keep more options open regarding ways of realizing / supporting those goals and activities. Manual workarounds can be a good alternative more often than you’d think.

- It augments rather than replaces practices from e.g. Scrum or eXtreme Programming and it plays well with techniques like Event Storming, which provides input for activities and tasks, Dimensional Planning to slice releases, and Example Mapping to carve out user stories and tests.

Further reading

- In his book The Product Owner’s Guide to Escaping Legacy, our colleague Wouter Lagerweij describes an approach to working with legacy systems which leverages story mapping.

- Jeff Patton offers useful materials on story mapping.

- Dimensional Planning is a useful way to slice releases, based on what’s good enough and what you are willing to pay for.

This is an updated version of a blog post that we published earlier in 2009.